Dunkin Donuts Trashed By Rumble; Review of book: Socialism As A Secular Creed: A Modern Global History; Creed defined

—

Review of book: Socialism as a Secular Creed: A Modern Global History

[I have written in several blog posts that Andrei Znamenski is a friend of mine. He is Polish Russian, from St. Peterburg, Russia. He moved to the United States in1991. He has a PhD in History from an American University and is a professor at the Univeristy of Memphis.

When you read the below review of the book, you will learn that he has written books about religions other than Christianity. Please don’t be put off by this because he is a historian, and he learned about the history of these religions and their place in the secular world and the impact on society.

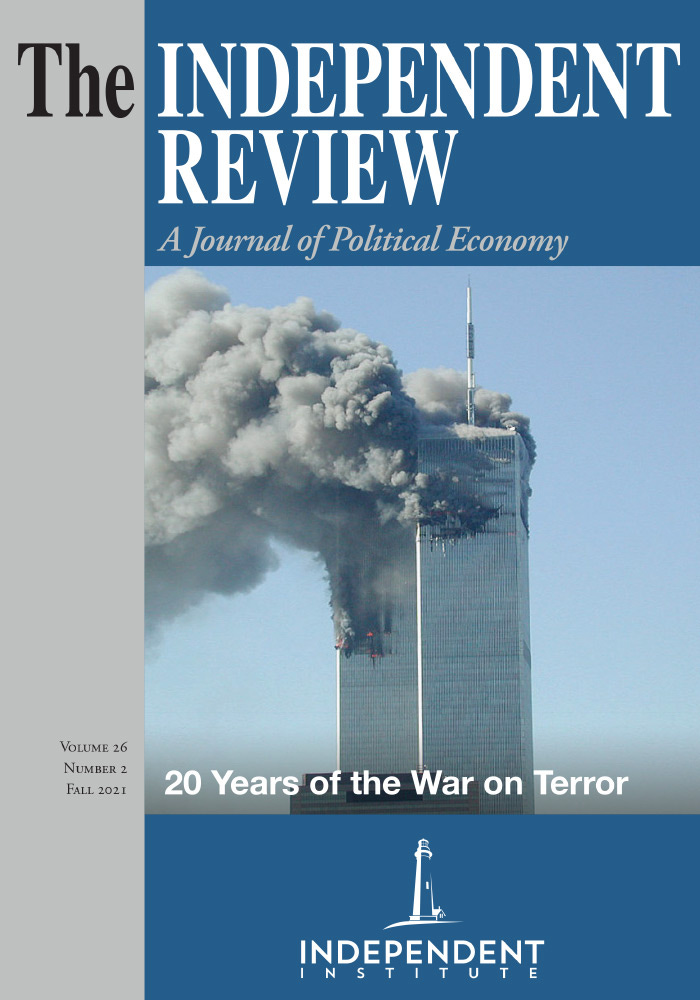

This review was published in the Independent Review. I recommend that you open the link and read all of the review. - JRD]

By Andrei Znamenski

Published:Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2021Pages:xlii, 450Reviewed by: Paul Dragos Aligica; University of Bucharest and George Mason University

[Socialism is a religion. - JRD]

“‘When I embarked on this project of galloping through the 150 years of socialism’s history,’ writes Andrei Znamenski in the introduction of this book, ‘I never suspected that it would be such an exciting and intellectually challenging venture’ (p. xxxii). The same thing may be said by the reader, after going through the 450 pages of a veritable tour de force in historical knowledge, analysis and interpretation.

Znamenski, a historian of religions and culture whose work has explored Christianity, Shamanism and Tibetan Buddhism, both in their doctrinal and their institutional and social manifestations, is exceptionally positioned to apply the secular religion framework in his studies of socialism. Moreover, he is a scholar who has a first-hand experience of a real-life socialism regime, being born and partially trained (including in Marxism) in the Soviet empire. Thus, in a sense, the book may be seen as part of a lifelong effort of trying to understand a personal experience that has marked him intellectually and existentially. Znamenski is not a dogmatic external critic. He’s a careful, thoughtful, critical thinker who is trying to make sense of a phenomenon he experienced from inside. The result is a fascinating book.

Socialism, writes Znamenski, is a form of political religion, “a secular creed that emerged with the rise of [the] modern world and became its radical manifestation” (p. xiii). It is a result of the twin belief in the industrial revolution and in science while at the same time, it is a reaction to the impact of the industrialization and the scientific rationalization of the world. The book traces the history of this phenomenon that has roots in the belief systems of human beings but that has formidable economic, political and institutional implications.

The structure of the book is straightforward. It follows chronologically the evolution of the socialist phenomenon from the nineteenth century to present. Each major episode in the evolution is marked by a chapter and each chapter, notes the author, should be read like an essay in interpretation. The result is both a chronological interpretation of the development of socialism in modern history and a set of essays dealing with socialism.

The first major theme of the book is, obviously, socialism as a secular creed, as a surrogate religion. The book explores the process by which traditional religion lost social influence—it became marginalized—while at the same time, the void created by this process was filled by the faith in scientific prophecies. At the same time, it tracks down the link between the cult of science, secularization and the rise of the omnipotent state as an instrument of social engineering. Thus, we reach the point, in the twentieth century, when the appeal to the authority of science ‘became for various ideologists a standard practice used to justify various grand projects of social engineering, mass mobilization, deportations, and social welfare schemes they advertised as progressive and benevolent’ (p. xxv). Out of the worship of science, technology, and state has emerged a formidably resilient collectivist project of social, cultural and even biological engineering which has survived the failure of the grand social experiments that it inspired to in the twentieth century. In brief, although framed as a historical overview, the book is, in the end, about the present and the future.

Since the secular religion of socialism was the child of modernity, explains Znamenski, one needs to address the relationship between modernity and the sacred. That is in fact the second dimension of the project: a modernization-studies perspective on socialism as a secular religion. Although the author distances his interpretations from some modernization theorists, the very fact that he is incorporating modernization theory lenses into the secular religions approach generates a powerful distinctive framework which situates this book in a class by itself, within the relevant literature.

That being said, this combination of ‘modernization theory’ and ‘socialism as secular religion’ perspectives is not the sole important contribution of this remarkable book. A major contribution comes from its path-breaking effort to methodically explore the emergence of the identarian left on the current public scene in the West, while illuminating its intrinsic link to the classical socialist movement. This is the point where the book becomes particularly relevant for our understanding of the current circumstances.”

Open link for remainder of book review:

—

Creed

“Creed, an authoritative formulation of the beliefs of a religious community (or, by transference, of individuals). The terms ‘creed’ and ‘confession of faith’ are sometimes used interchangeably, but when distinguished ‘creed’ refers to a brief affirmation of faith employed in public worship or initiation rites, while ‘confession of faith’ is generally used to refer to a longer, more detailed, and systematic doctrinal declaration. The latter term is usually restricted to such declarations within the Christian faith and is especially associated with churches of the Protestant Reformation. Both creeds and confessions of faith were historically called symbols, and the teachings they contain are termed articles of faith or, sometimes, dogmas.”

—